Political Debates: Where Presence Speaks Louder Than Words

When we speak to someone, it is essential that we convey the same message through our body language and facial expressions.

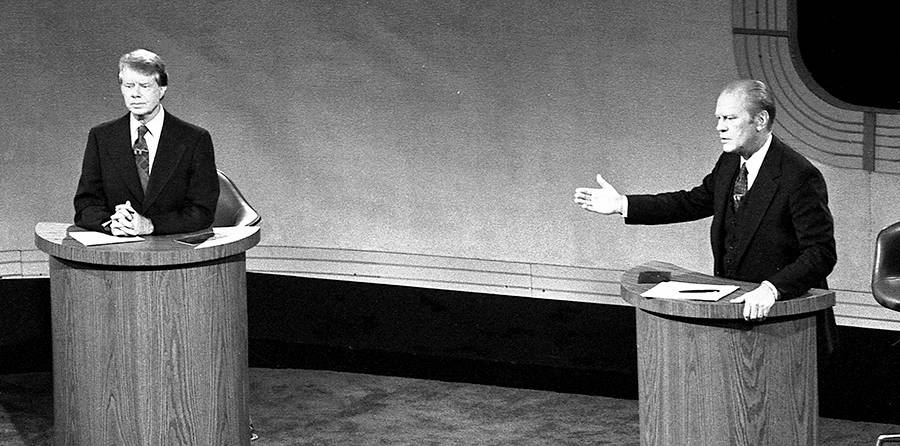

Presidential debates are a perfect example of how important it is to pay attention to ones stage presence. Many candidates spend time and money developing innovative policies, only to sabotage them on delivery through their physical behavior or tone of their voice.

This first hurt Richard Nixon in the televised debate between him and John F. Kennedy in 1963. Nixon’s nervous demeanor—he constantly wiped sweat from his brow throughout the debate—undermined his message to the voters and Kennedy was considered the clear winner by the television audience. Interestingly, those who listened to the debate on the radio gave the edge to Nixon because his voice and message were compelling—and were not undermined by his body language and appearance.

A quote from a Boston Globe story reinforces the point. “The twitchiness is seen unconsciously by the viewer/voter as reflecting on the personality [of the candidate],” said Joseph Tecce, a psychology professor at Boston College who studies nonverbal communication. “It can influence the viewer’s vote.” The home television audience was able to factor in the inherent flaws of Nixon’s delivery—ignoring his words and focusing instead as we typically do on his body language.

So how much of our communication is actually attributed to our words? According to Dr. Albert Mehrabian, the author of Silent Messages, only 7% of any message is actually conveyed through words. Another 33% is conveyed through vocal elements (pitch, tone, etc.) and a whopping 55% is through nonverbal elements (facial expressions, gestures, and posture).

When we speak to someone, it is essential that we convey the same message through our body language and facial expressions. By using expressiveness (pitch, tone, facial expressions, and gestures), you provide your audience with information and clues to understand how they should feel in the situation. Keith Johnstone, considered many as the father of Improvisational Theater, has a lot to say about this. Johnstone was very interested in the “status” an audience infers from the slightest change in their physical behavior. His “signals of status” are taught in Improv classes around the world and form the basis for the great work at Second City and Improv Olympics.

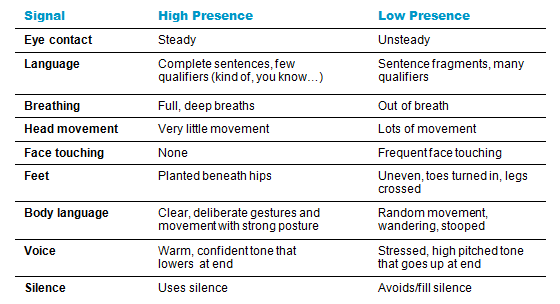

Johnstone’s signals (see box below) can seem simple on the surface but even the slightest change in any one of them can change an audience’s perception of the speaker from someone they admire, respect and trust to someone not worth listening to.

SIGNALS OF PRESENCE – Adapted from Keith Johnstone’s signals of status

Standing still, breathing evenly, and maintaining steady eye contact has a profound impact on an audience. Johnstone says the following, “Our behavior–reinforced by our appearance–signals our importance or lack of importance.” And he goes on to say, “No behavior is insignificant. When we interact together, our brains are counting the blink rate and registering even the tiniest head movement.”

George H. W. Bush infamously looked at his watch during the only debate he had with candidate Bill Clinton. To the audience, it appeared he as though he was bored and that what Bill Clinton was saying wasn’t of interest. It looked like he “had better things to do than this.” His second—no pun intended—of non-engagement that night is to have said to have lost him the election.

The implications are clear when the stakes are as high as they are during presidential debates. But they are equally relevant in our daily interactions? Think about your next job interview, a presentation to your team, or an interaction with your spouse. What message do your signals of presence say about you? And do they support or undermine your message?

You need more than just a compelling message to reach the heart as well as the head of an audience.